Why Planting More Street Trees Isn’t the Answer to Climate Change

Mar 5, 2023

Recently I came across a study that confirms it, our street trees live fast and die young. The research shows, that urban trees (in comparison to their rural counterparts), experience (4x) accelerated growth and double the mortality rates. All of this means that we are experiencing a net loss in carbon storage, over time. According to the study, “The findings suggest that planting initiatives alone may not be sufficient to maintain or enhance canopy cover and biomass due to the unique demographics of urban ecosystems.”

(sciencedaily, PLOS. (2019, May 8). Urban trees 'live fast, die young' compared to those in rural forests: Unusual features of street-tree life cycles should inform urban greening campaigns. ScienceDaily. Retrieved March 21, 2023 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/05/190508142450.htm)

Having worked in the parks system for a dozen years, I have often seen city councils use trees as a major part of their platform to combat climate change. I understand the thought: trees are good for the environment, therefore loads of trees are even better, right? Except that nature is never that simple. Every year, I witnessed a huge number of saplings planted in every available green space around the city, and every year a good half of them would die and require removal. And yet, the cities annual tax update would proudly announce how many hundred trees had been planted. Period.

More and more there seems to be a genuine disconnect between an exciting soundbite on the news, and the complex reality that sits below the surface. It’s this kind of green washing that has brought trouble to our doorsteps and may well get worse if we don't look deeper.

I've always found it easier to confront issues, when I can understand where they stem from. So today, we'll begin with a brief history of urban forestry, up to the present day. Then, we can delve into a few of the main issues effecting plant health and take on some case studies that offer a range of solutions. We may be in a challenging position, but it is far from insurmountable.

History of Urban Trees

The idea of urban trees can be traced back through time.

- The ancient Egyptians, used pits to recreate the natural conditions for the growth of trees from distant ecosystems. Hence, trees from the fertile soils along the Nile could be grown within the dry desert gardens of Amarna.

- In medieval times, monastic complexes included green spaces featuring equidistant fruit trees, seasonal flowers and oddly, graves (but that’s another story).

- And, the 17th and 18th centuries saw the first purposely planned promenades and boulevards appear in Paris, quickly becoming a leisure space for society to comfortably stroll beneath beautiful shade trees.

Side note

The street trees of Paris were so influential that many of our descriptive urban terms have French origins, including: Boulevard, Avenue and Alley (allée). All various types of tree lined roadways.

But I digress, when we really see the modern vision of urban trees come into being, is within the last 150 years or so.

As cities came into the modern age, roads were expanded to accommodate carriages (and eventually automobiles). Communal utilities required the collective installation of power, water and sewer, above and below soil level. And, industrialization began to change how we used and built our cityscapes.

Prior to the advent of paved roads, 'tree lawns' gained popularity. These living barriers sat in the space between the sidewalk and the often muddy street. Trunks offering protection from the splashes of passing vehicles, and canopies, shade for passers by and horses alike. In turn, iron 'tree guards' were later added to deter vandalism from restless hungry horses.

Soon, tree-lined streets began popping up as cities expanded across the new world and were rebuilt and renewed throughout Europe. Eventually becoming a standard feature of western-inspired cityscapes across the globe. With many colonial outposts featuring hugely diverse tree collections, reflecting their expansive empires.

This is also the time that the great parks of the world were being built in response to the poor sanitation and pollution that became tantamount to industrialized cities. Early designers such as, Frederick Law Olmsted, saw that these 'airing grounds' could also be decorated with a carefully standardized vision of beauty. Through symmetry and repetition a sense of value was formed, giving viewers an easily read language of tidy beauty. Naturally, these concepts then extended to include streetscapes, spreading the value of greenery throughout a city.

Modern Specs

Over time, what began with the beauty of progress eventually became a contentious subject. Street trees sit at the intersection of local politics, private and public lands and community planning and development. As dirt streets were paved and land costs increased, tree lawns have gradually become smaller and smaller, reduced to thin strips or mere grates in the concrete.

These days, most cities have specific requirements and guidelines for all urban trees. From the species selected to its placement. From the surrounding infrastructure to its maintenance. City trees are subject to a huge list of restrictions placed on them by planners and engineers that may not fully appreciate the complexity of their living requirements.

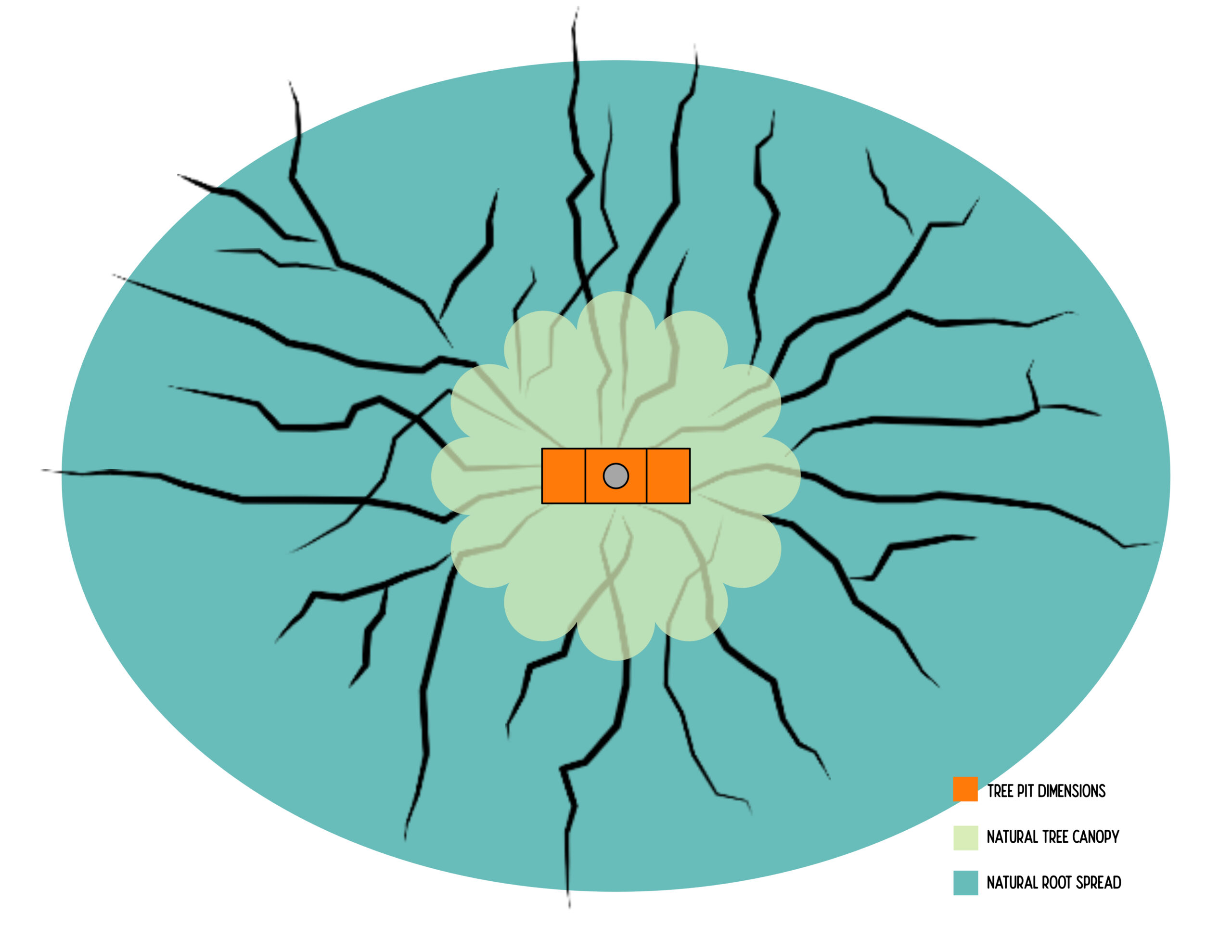

For instance, many current building techniques include 1 meter (or less) cubed tree pits surrounded by highly compacted road underlay, concrete or other root barriers. Each tree sat in its own enclosed space, with limited water and oxygen, devoid of living soil and companion plants.

As an example, my own hometown suggested (as recently as 2011), planting Acer campestre ‘Queen Elizabeth’ (field maple). Which is noted as a “medium” tree suitable for sidewalk plantings as diminutive as 3’ (90cm). According to the Wurtzelatlas (Root atlas), a rural field maple at a height of 14 m (46 ft) was found to have a root system spread of 13.5 m (44ft) x 18 m (59 ft) and depth of 3.5 m (11 ft).

When we combine this information with the architectural drawings that the city provided for street planting, several key issues immediately become apparent. It's a bit like a caged elephant. Can they survive in there, barely; will they thrive in that environment? Absolutely not. And this is just one of the issues that street trees must overcome. Let's break it down a little more and add a few fascinating case studies to get a broader view of things.

Plant Choice

We choose our urban trees with a set of characteristics that are entirely unique and constantly in flux. This complexity can have far reaching consequences, since choosing an incompatible species can reduce a trees natural lifespan of 30-40 years, to just 7-14.

Some considerations include:

- available space

- climate conditions and extreme weather events (current and future)

- resistance (to pollution, compaction and drought, disease and road salt)

- lack of invasive traits

- beauty, fragrance and seasonal interest

- maintenance requirements

- the ability to mitigate urban heat

- commercial production and availability of plant stock

Over the years, many species that were once popular, are no longer being planted. For instance, the tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima), has been rejected because of its pungent odour. Many elms (Ulmus) have been lost to disease. Norway maples (Acer platanoides), are prodigious self seeders. And, a great number of females of various species were rejected because they’re considered messy. Dropping fruit, seeds and pods, that may provide food for wildlife but also require regular cleanup. This has inadvertantly increased seasonal hay fever, due to the volume of pollen that is released by the overwhelmingly male tree population.

Some cities have begun to address these issues, including Vancouver, where a list of 300 tree species has been compiled, thought to be more resilient to continuing climate change. Others have limited the number of same family, genera and species to be planted overall, in order to maintain diversity and limit disease loss. In addition to the inclusion of lesser used varieties and native species or navitars (native cultivars), that can be commercial produced.

City of Melbourne

A unique collaboration has lead to a new way of choosing plant material for the city of Melbourne. Parks and Greening departments began by approaching university academics to identify a range of suitable species based on various future climate scenarios. When they realized that many of the suggestions weren’t readily available, local industry professionals joined in to source and grow potential plant material. The resulting trees, are then trialed on low key sites around the city, where they can be monitored and assessed in situ, prior to wider distribution.

The result is the formation of a symbiotic relationship between the city and the nurseries that supply them. City staff are able to specify the numbers, quality and species of trees that they want. Meanwhile the nurseries, not only get contracts, but provide important feedback that ensures the best possible success for urban projects.

Placement and Infrastructure

Standard planting requirements are usually set by city engineers and given to developers and citizens in the form of guidelines. But as we’ve seen, this can be problematic. As extreme weather events continue, we’re seeing greater losses of mature street trees. During a wind storm in the fall of 2022, the city of Vancouver lost 400+ trees. Many of which had survived to maturity, but weakened by summer droughts and other urban stressors, toppled over. And unfortunately, our city is not alone.

Over the last few decades, several ideas have emerged that can improve the health and longevity of street trees throughout their lives. These include:

- access to stormwater systems, rain gardens and bioswales

- extended soil vaults/cells to reduce compaction and provide more root space

- engineered soils

- the addition of biochar

- reduced numbers planted in extended tree pits

- adding perennial and annual plants to build communities

- interspersing street trees with vertical solutions like vines

The Stockholm Solution

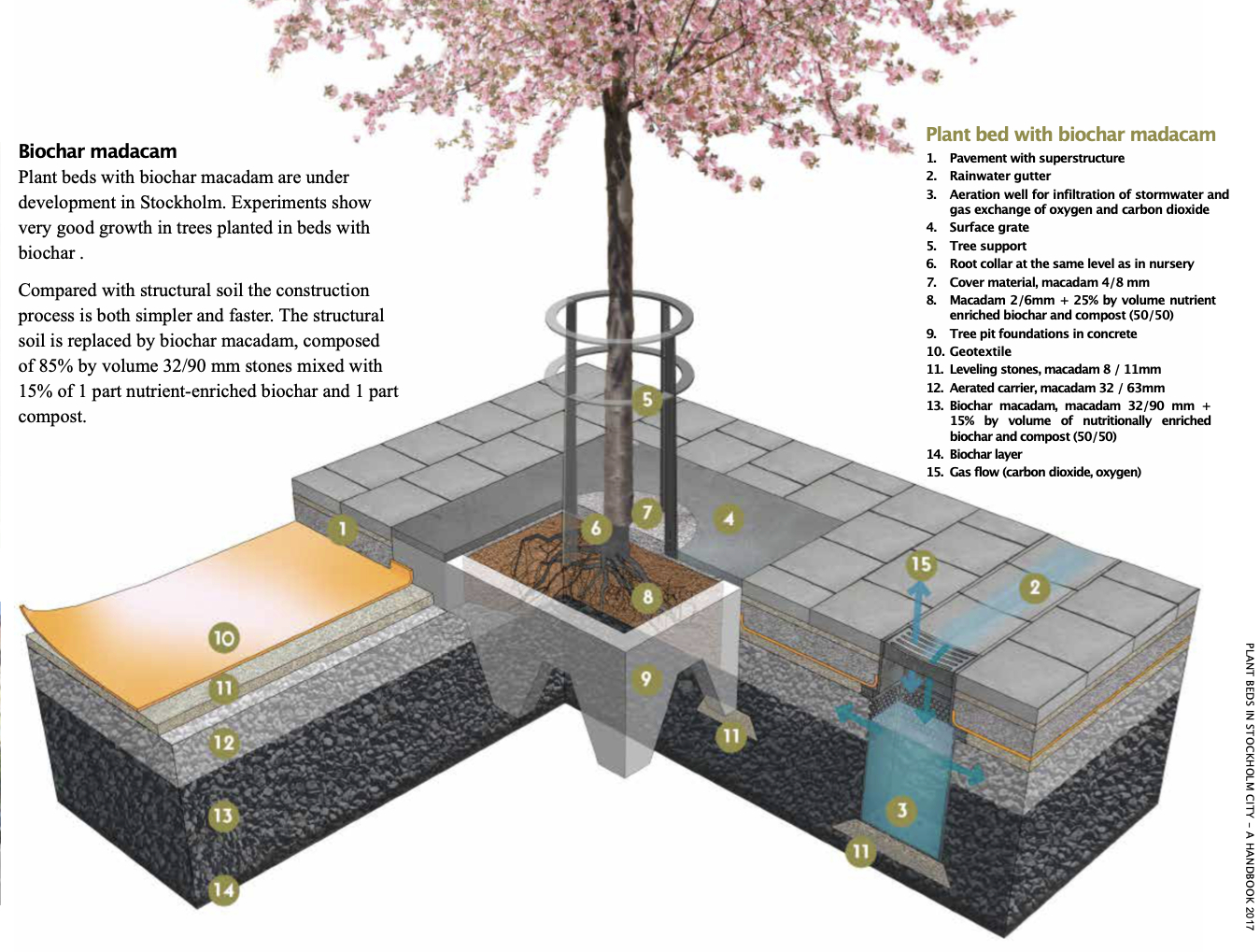

In 2001, a study showed that 2/3rds of Stockholm’s urban trees were either dead or dying and a solution was needed urgently. So after years of conventional construction, a new system emerged. Named after the city itself, the Stockholm Solution, is an entirely new way to manage urban trees and storm water. The goal is to, “plant beds that are sustainable and has (sic) minimal environmental impact on the basis of material and design, simple design for secure results, low operating costs, a final product where trees and plant beds is (sic) part of the city's environmental efforts.”

It starts with a unique layering system of structural soil, drainage and geotextiles. Which means that while the sidewalk surface is stable and safe, underneath tree roots can stretch out to accommodate mature growth. Utilities are safeguarded, limiting disturbance while air and water are allowed to infiltrate. At the same time, there are additional features to redirect stormwater, mitigating water loss and flood danger.

It starts with a base layer of larger sharply angular pieces of 32/90 mm granite or recycled concrete, which will remain rigid while maintaining and protecting pockets of air, water and soil (which is washed in during installation). Further helped by aeration wells that connect the layers with the surface level, feeding the whole of the root layer and allowing gas exchange.

The tree itself is installed with a unique concrete support crate that directs roots away from the surface while providing stability. Then a drainage layer is brought up to the sides of the crate and above the structural level. The smaller angular 32/63 mm rock helps to further distribute surface air and water throughout the area. Then a geotextile helps to keep surface roots contained and the drainage layer free of surface paving materials.

The inclusion of biochar has also not only improved soil quality and water filtration, but has the added attraction of acting as a further carbon trap. It comes from a sister project, where municipal greenwaste can be converted into biochar, closing another loop within the logistics of the city itself.

Darwin Shade Structure

Installed in 2018, the Cavenagh St Shade Structure is part of a greater scheme to mitigate heat issues in the tropical city. It’s a canopy that stretches to cover an expanse 23m (75') wide by 55m (180') long, connecting one side of the busy thoroughfare to the other. Constructed on a skeleton of metal girders with a vaulted timber lattice and cable system. The idea included the planting of some 20 vines (Rangoon Creeper and Orange Trumpet) that would grow from several central containers to eventually cover the structure.

As of 2023, the reviews have been mixed. With many citizens questioning the costs associated with the structure vs the efficacy of it. The vines have been slow to cover the huge structure and there are some questions as to plant choice and placement. However, that being said, I feel like the concept is still viable with many other similar, if smaller, shade structures continuing to be built quite successfully.

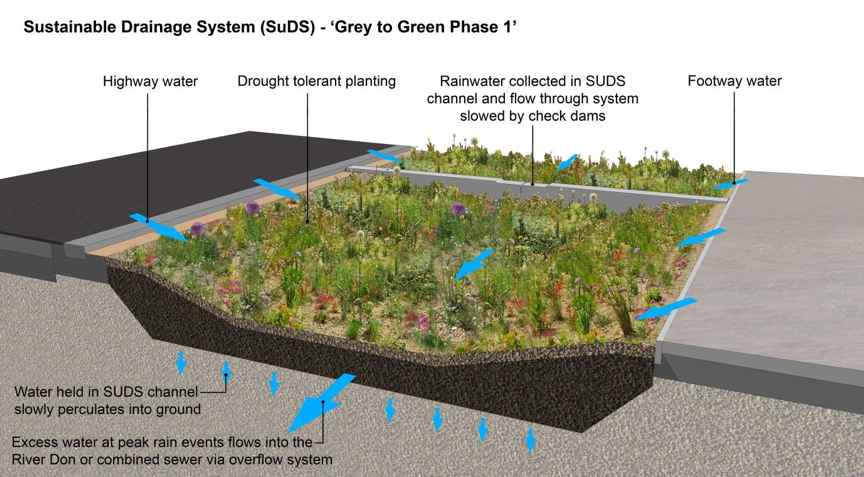

Sheffield Grey to Green

One project that I’ve talked about before, Grey to Green, represents some really key strategies for ecological street greening. Here we see a series of larger bioswales and rain gardens that run along city streets and walkways. Utilizing SuDS (sustainable drainage systems) techniques, they all connect and include mini dams, engineered soils and plantings to slow and encourage the absorption of stormwater. But most interestingly in this case, is the way that trees are mixed with other plant material in order to build novel ecosystems. This mimics the way that plants work in the wild; fixing, storing and sharing nutrients and information that leads to greater overall resilience and adaptability.

Pruning and Maintenance

The long term maintenance of plantings is another key element to their overall success. In the past this aspect was often overlooked, but now many forestry programs have begun to give up short term gains for longterm stewardship, but there are always new ideas emerging:

- choosing structural pruning over reactive

- limited additional watering to maintain the natural resilience of drought tolerant varieties

- planting trees bare root to encourage adaption and infiltration into existing soils

- using soil/compost teas to kick start soil health

- directional pruning for utilities, rather than topping

- utilizing the community to monitor tree health

- programs to encourage the public to see the value of urban trees and green spaces

- tech solutions for monitoring and the simulation of overall health, canopy cover and heat reduction

- signage to engage and provide explanations

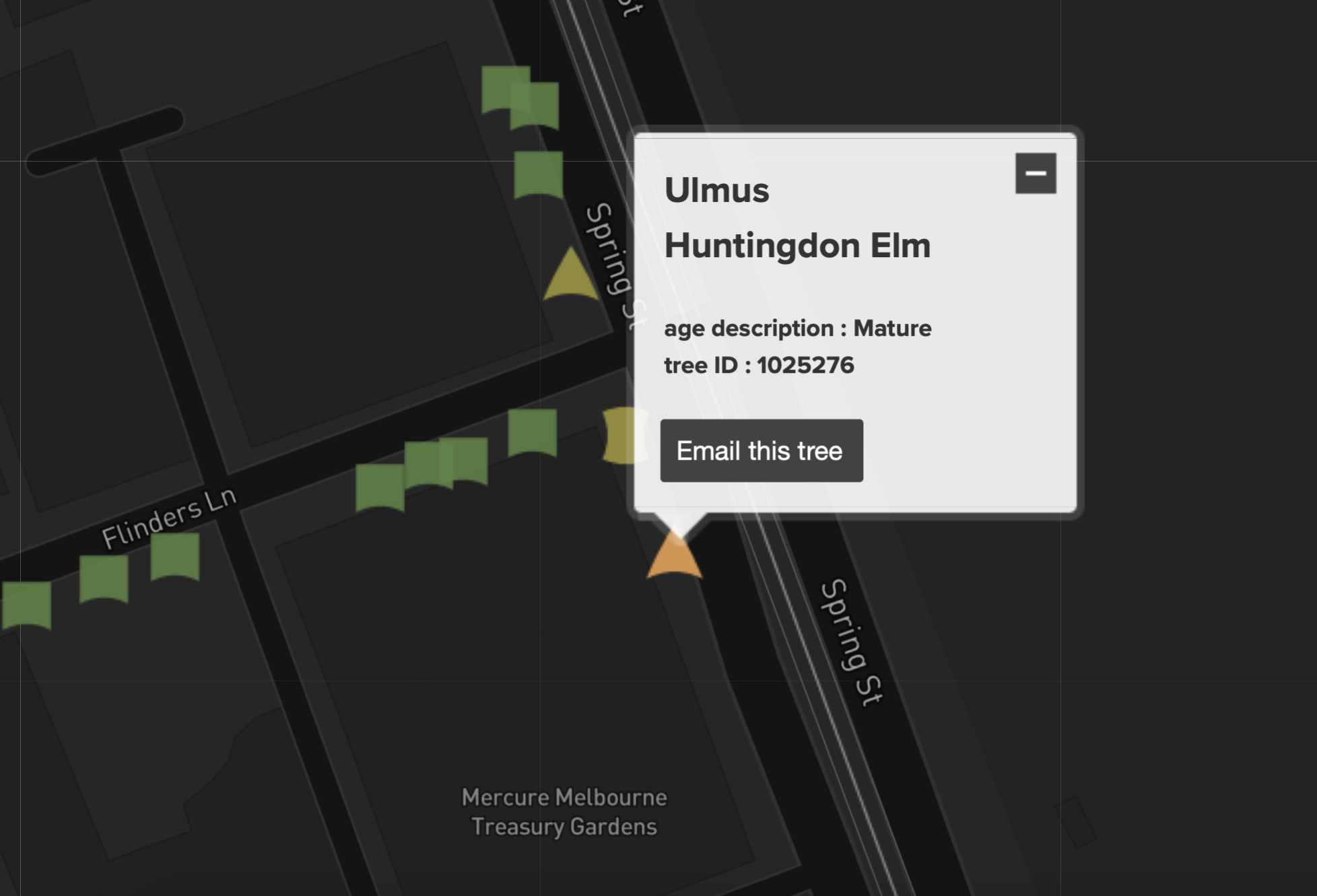

Melbourne Visual Forest Map

In 2013, Melbourne further cemented itself as a leader in city greening when it introduced, the Urban Forest Visual. It includes a digital map showing every one of the 80,000 trees in the cities parks and streets. Detailing their species, age and current health. Each tree has also been allocated with it’s own unique email that allows the public to help monitor the trees health and alert city workers to any issues.

Shortly after its installation, there was a surprising development. Rather than the expected reports of damaged bark and downed branches, the treemails became an outlet for users to share personal messages with the trees themselves. Highlighting the therapuetic value that the public attaches to communal green spaces. Some of the messages include:

- good luck with the photosynthesis

- I very fond of you (sic)

- I miss you

- It makes me happy knowing you are there

- It saddens me that your passing will be sooner than my own

- You are beautiful. Sometimes I sit or walk under you and feel happier.

I love the way the light looks through your leaves and how your branches come down so low and wide it is almost as if you are trying to hug me. It is nice to have you so close, I should try to visit more often.

You are my favourite tree because you are a native, standing proud in a cultivated English garden of colonising trees, imported to remind settlers of a home they may never return to. You remind me to be as strong and beautiful as you are. - Dear 1517937,

I am confessing something very dear to me. I have fallen in love with 1583182. I also feel guilty for cheating on 1023379 but yet I justified it on the fact that 1023379 is expected to die in under a year. I honestly feel really bad and I don’t know what to do, it would be really great if you could give me some advice. Should I wait for 1023379 to die or should I leave 1023379 for 1583182.

Regards, A Tree Lover <3

Once the degree of interest from the public was realized, the city began to include them in more involved aspects of arbour care. Residents can now register to become, Citizen Foresters, and participate in a variety of projects from surveys and mapping to planting habitat areas.

At the moment, our urban trees are releasing more carbon than they're trapping, directly contradicting the idea that simply planting more trees is a linchpin in the fight against climate change. But all is not lost, if we are able to slow down and address current urban forestry practices, we can improve as we move forward. If we are able to make better more collaborative choices in plant material, placement, infrastructure and tree maintenance (even if it means planting less trees overall) success can still be attained. So the next time that your city offers a quick fix eco-plan, you too can spot the greenwashing and take action.

P.S. Is anyone else wondering if 1023379 got dumped for 1583182?

Sara-Jane & Alicia at Virens Studio

Virens is a studio based in Vancouver, Canada, that specializes in Ecological Planting Design, Urban Greening Consultation and Garden Writing. Visit our site today and don't forget to follow us on social media and Substack.

© Virens Studio 2025 (all photos are used for demonstration purposes and do not necessarily belong to us.)

What’s a life lived without any vices, dirt or messiness? I might reply, boring. Because, when I think about it, what’s more interesting to witness and be a part of? Think of a classy soirée. Where everyone arrives dressed to impress, with manners to match. On their best behaviour, that is, until late into the…

Are You a Lazy Gardener? Or, a Habitat Hero?

I’ve been working as a gardener and landscape designer for nearly 20 years. In some ways, I find this hard to believe (there’s more to learn) and also totally true (when I think back to some of the things that I was doing in my first years in the Parks Department). But I digress, what…

How I Choose Plants (as a Professional Landscape Designer)

I see people slowing down for a good long look at my new garden. And as I clock their movements, in my mind I can hear them saying, “what kind of landscaping is that?, the plants are all soooo small and what’s with all the sand?!” Well, as a planting designer, former parks gardener and…